Key Facts

Imagine a boardroom where a critical strategic error has just come to light. In Company A, the room goes silent. Eyes dart downward. The focus immediately shifts to “who is responsible” so that blame can be assigned and the “guilty” party can be managed out. In Company B, a hand goes up. “I think I missed a signal in the Q2 data,” a VP says. “Here’s what I learned, and here’s how we can pivot.” The room exhales, and the team immediately begins brainstorming solutions.

Company B isn’t just “nicer.” It is faster, more resilient, and more innovative. This difference is the tangible result of psychological safety.

For years, psychological safety was viewed as a “soft” perk—a nice-to-have cultural add-on. Today, thanks to extensive research including Google’s Project Aristotle, we know it is the single most important predictor of high-performing teams. For the Chief Human Resources Officer (CHRO), moving an organization from the fear-based culture of Company A to the learning-based culture of Company B is not just an HR initiative; it is a strategic imperative.

Beyond “Nice”: Defining Psychological Safety for Leaders

Before a CHRO can architect a culture of safety, they must clarify what it is—and crucially, what it is not.

Harvard Business School professor Amy Edmondson defines psychological safety as “a shared belief held by members of a team that the team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking.” It is the assurance that one will not be punished or humiliated for speaking up with ideas, questions, concerns, or mistakes.

However, a common misconception exists that psychological safety equals “comfort.” In reality, a high-performance culture requires productive discomfort. If employees are comfortable but not challenged, the organization drifts into the “Comfort Zone,” where engagement is high but results are stagnant. The goal for the CHRO is the “Learning Zone,” where high psychological safety is paired with high accountability.

The Four Stages of Safety

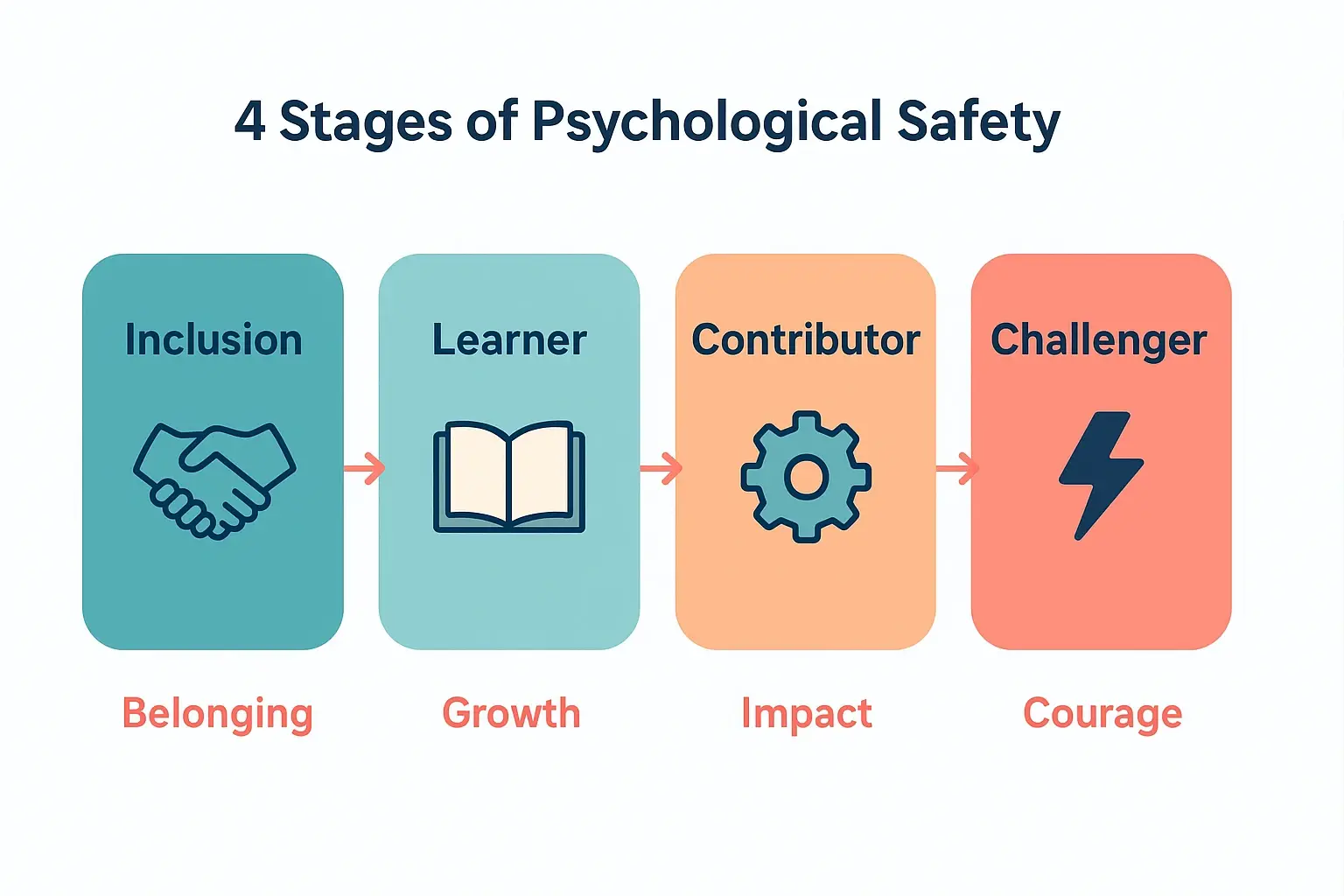

To operationalize this, it helps to view safety not as a binary switch (safe vs. unsafe) but as a progression. Social scientist Timothy Clark outlines four distinct stages that an organization must traverse:

- Inclusion Safety: Members feel safe to belong to the team.

- Learner Safety: Members feel safe to learn through asking questions and making mistakes.

- Contributor Safety: Members feel safe to contribute their own ideas and skills.

- Challenger Safety: Members feel safe to challenge the status quo and leadership without fear of retribution.

The CHRO’s Mandate: From Policymaker to Cultural Architect

Why does this fall squarely on the CHRO? Because psychological safety cannot be sustained by individual managers alone. While a team leader can create a “pocket” of safety, a systemic lack of safety usually stems from organizational root causes: rigid hierarchy, fear-based performance management, or a lack of integral leadership capabilities at the executive level.

The CHRO acts as the architect, designing the environment where these four stages can flourish. This involves shifting the HR function from policing policy to enabling honest human connection.

The Business Case for the C-Suite

When advocating for this cultural shift, the CHRO must speak the language of business resilience.

- Innovation: Innovation requires failure. Without safety, employees hide failures rather than learning from them.

- Risk Management: In unsafe cultures, bad news travels slowly. By the time leadership hears about a critical issue, it is often too late.

- Talent Retention: Top talent demands autonomy and a voice. If they cannot challenge the status quo (Stage 4), they will leave for a competitor where they can.

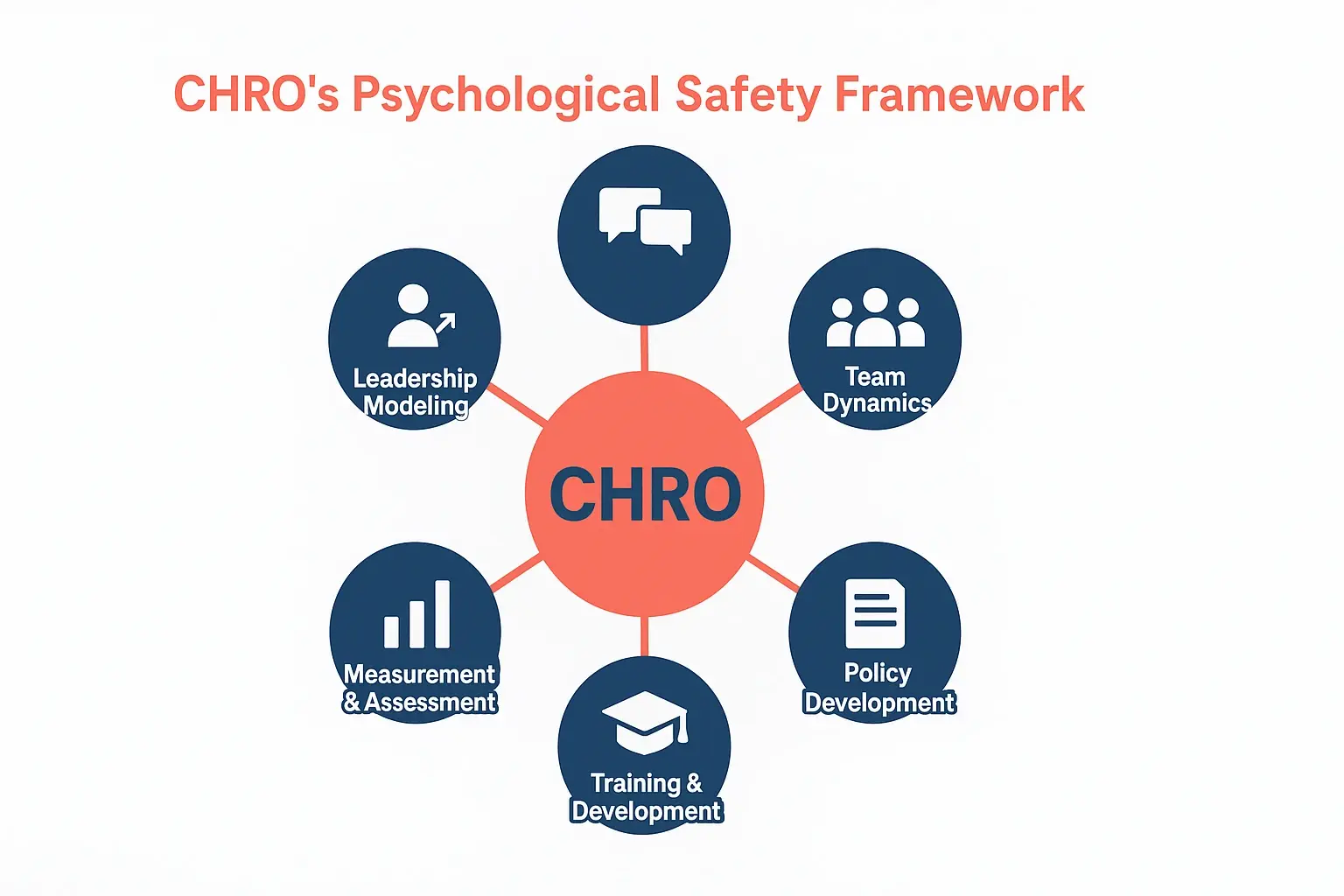

Strategic Implementation: The Six Pillars

Fostering psychological safety is not achieved through a single workshop. It requires a comprehensive strategy that touches every aspect of the employee lifecycle.

1. Modeling Vulnerability at the Top

Safety flows downward. If the C-suite never admits a mistake, no one else will. The CHRO must coach the executive team on executive presence and influence, teaching them that admitting “I don’t know” or “I was wrong” is a display of strength, not weakness. This behavior signals to the organization that fallibility is human.

2. Reframing Work as Learning Problems

In a traditional execution model, work is a series of tasks to be completed correctly. In a psychological safety model, work is viewed as a series of experiments. The CHRO helps leaders reframe language. Instead of asking, “Why did this go wrong?” leaders are trained to ask, “What did we learn from this result?”

3. Decoupling Fear from Accountability

This is the most challenging pillar. How do you hold people accountable without generating fear? The answer lies in transparency. When evaluation criteria are opaque, anxiety spikes. The CHRO ensures that success metrics are clear and that performance conversations focus on development rather than judgment.

4. Designing For Candor

Open dialogue doesn’t happen by accident. It must be designed into the workflow. This might look like “After Action Reviews” (AARs) where titles are left at the door, or “Red Teams” assigned specifically to punch holes in a proposed strategy. These structures normalize the integral team dynamic of constructive conflict.

5. Managing the “Dark Side”

The CHRO must also be vigilant against the misapplication of safety. Psychological safety does not mean “anything goes.” It does not mean freedom from consequences for negligence or violation of ethics. A crucial part of the CHRO’s role is clarifying the boundaries—safety protects the person, not the poor performance.

6. Measuring the Invisible

You cannot manage what you do not measure. However, standard engagement surveys often miss the nuance of safety. CHROs are increasingly using specific pulse questions such as:

- “If you make a mistake on this team, is it often held against you?”

- “Is it safe to take a risk on this team?”

- “Do you feel able to bring up problems and tough issues?”

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Doesn’t psychological safety lower standards?A: No. In fact, it raises them. When people feel safe, they are more likely to ask for help when they are stuck, admit when they are overwhelmed, and point out defects in products before they ship. Low safety often hides low standards behind a facade of compliance.

Q: How do we build this in a hybrid/remote environment?A: Remote work removes the visual cues of safety (a nod, a smile). Leaders must be “intentionally explicit.” In a virtual meeting, silence does not mean agreement. Leaders must actively solicit dissenting opinions (e.g., “What are we missing?” rather than “Does everyone agree?”).

Q: What if I have a toxic leader who delivers high numbers?A: This is the ultimate test for the CHRO. Tolerating a toxic high-performer destroys psychological safety for everyone around them. To build a true culture of safety, the organization must be willing to coach—and if necessary, part ways with—leaders who destroy trust, regardless of their short-term output. This aligns with purpose-driven leadership principles.

Q: How long does it take to change the culture?A: Building trust is a slow process; destroying it is fast. While you can see shifts in team micro-climates within months, an organizational transformation led by the CHRO typically takes 18 to 24 months of consistent reinforcement, training, and policy alignment.

The Path Forward

For the modern CHRO, fostering psychological safety is not about wrapping employees in cotton wool. It is about removing the brakes on performance. It is about creating an environment where the collective intelligence of the organization is fully unlocked because people are no longer spending their energy managing their image or hiding their mistakes.

By understanding the mechanics of safety, from the four stages of inclusion to the nuances of executive modeling, HR leaders can transform their organizations into resilient, innovative engines of growth. The journey requires patience and integral coaching at all levels, but the destination—a high-performance culture that thrives on truth—is worth the effort.